SOLID design principles: Building stable and flexible systems

Posted Jan 17, 2019 | 15 min. (3024 words)To build stable and flexible software, we need to keep software design principles in mind. Having error-free code is essential. However, well-designed software architecture is just as important.

SOLID is one of the most well-known sets of software design principles. It can help you avoid common pitfalls and think about your apps’ architecture from a higher level.

Raygun lets you detect and diagnose errors and performance issues in your codebase with ease

What are SOLID design principles?

SOLID design principles are five software design principles that enable you to write effective object-oriented code. Knowing about OOP principles like abstraction, encapsulation, inheritance, and polymorphism is important, but how would you use them in your everyday work? SOLID design principles have become so popular in recent years because they answer this question in a straightforward way.

The SOLID name is a mnemonic acronym where each letter represents a software design principle, as follows:

- S for Single Responsibility Principle

- O for Open/Closed Principle

- L for Liskov Substitution Principle

- I for Interface Segregation Principle

- D for Dependency Inversion Principle

The five principles overlap here and there, and programmers use them broadly. SOLID principles lead to more flexible and stable software architecture that’s easier to maintain and extend, and less likely to break.

Single Responsibility Principle

The Single Responsibility Principle is the first SOLID design principle, represented by the letter “S” and defined by Robert C Martin. It states that in a well-designed application, each class (microservice, code module) should have only one single responsibility. Responsibility is used in the sense of having only one reason to change.

When a class handles more than one responsibility, any changes made to the functionalities might affect others. This is bad enough if you have a smaller app but can become a nightmare when you work with complex, enterprise-level software. By making sure that each module encapsulates only one responsibility, you can save a lot of testing time and create a more maintainable architecture.

Example of the Single Responsibility Principle

Let’s see an example. I’ll use Java but you can apply SOLID design principles to any other OOP languages, too.

Say, we are writing a Java application for a book store. We create a Book class that lets users get and set the titles and authors of each book, and search the book in the inventory.

class Book {

String title;

String author;

String getTitle() {

return title;

}

void setTitle(String title) {

this.title = title;

}

String getAuthor() {

return author;

}

void setAuthor(String author) {

this.author = author;

}

void searchBook() {...}

}However, the above code violates the Single Responsibility Principle, as the Book class has two responsibilities. First, it sets the data related to the books (title and author). Second, it searches for the book in the inventory. The setter methods change the Book object, which might cause problems when we want to search the same book in the inventory.

To apply the Single Responsibility Principle, we need to decouple the two responsibilities. In the refactored code, the Book class will only be responsible for getting and setting the data of the Book object.

class Book {

String title;

String author;

String getTitle() {

return title;

}

void setTitle(String title) {

this.title = title;

}

String getAuthor() {

return author;

}

void setAuthor(String author) {

this.author = author;

}

}Then, we create another class called InventoryView that will be responsible for checking the inventory. We move the searchBook() method here and reference the Book class in the constructor.

class InventoryView {

Book book;

InventoryView(Book book) {

this.book = book;

}

void searchBook() {...}

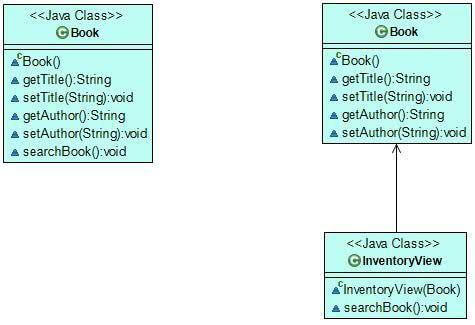

}On the UML diagram below, you can see how the architecture changed after we refactored the code following the Single Responsibility Principle. We split the initial Book class that had two responsibilities into two classes, each having its own single responsibility.

Open/Closed Principle

The Open/Closed Principle is the “O” of SOLID’s five software design principles. It was Bertrand Meyer who coined the term in his book “Object-Oriented Software Construction”. The Open/Closed Principle states that classes, modules, microservices, and other code units should be open for extension but closed for modification.

So, you should be able to extend your existing code using OOP features like inheritance via subclasses and interfaces. However, you should never modify classes, interfaces, and other code units that already exist (especially if you use them in production), as it can lead to unexpected behavior. If you add a new feature by extending your code rather than modifying it, you minimize the risk of failure as much as possible. Besides, you also don’t have to unit test existing functionalities.

Example of the Open/Closed Principle

Let’s stay with our book store example. Now, the store wants to hand out cookbooks at a discount price before Christmas. We already follow the Single Responsibility Principle, so we create two separate classes: CookbookDiscount to hold the details of the discount and DiscountManager to apply the discount to the price.

class CookbookDiscount {

String getCookbookDiscount() {

String discount = "30% between Dec 1 and 24.";

return discount;

}

}

class DiscountManager {

void processCookbookDiscount(CookbookDiscount discount) {...}

}This code works fine until the store management informs us that their cookbook discount sales were so successful that they want to extend it. Now, they want to hand out every biography with a 50% discount on the subject’s birthday. To add the new feature, we create a new BiographyDiscount class:

class BiographyDiscount {

String getBiographyDiscount() {

String discount = "50% on the subject's birthday.";

return discount;

}

}To process the new type of discount, we need to add the new functionality to the DiscountManager class, too:

class DiscountManager {

void processCookbookDiscount(CookbookDiscount discount) {...}

void processBiographyDiscount(BiographyDiscount discount) {...}

}However, as we changed existing functionality, we violated the Open/Closed Principle. Although the above code works properly, it might add new vulnerabilities to the application. We don’t know how the new addition would interact with other parts of the code that depends on the DiscountManager class. In a real-world application, this would mean that we need to test and deploy our entire app again.

But, we can also choose to refactor our code by adding an extra layer of abstraction that represents all types of discounts. So, let’s create a new interface called BookDiscount that the CookbookDiscount and BiographyDiscount classes will implement.

public interface BookDiscount {

String getBookDiscount();

}

class CookbookDiscount implements BookDiscount {

@Override

public String getBookDiscount() {

String discount = "30% between Dec 1 and 24.";

return discount;

}

}

class BiographyDiscount implements BookDiscount {

@Override

public String getBookDiscount() {

String discount = "50% on the subject's birthday.";

return discount;

}

}Now, DiscountManager can refer to the BookDiscount interface instead of the concrete classes. When the processBookDiscount() method is called, we can pass both CookbookDiscount and BiographyDiscount as an argument, as both are the implementation of the BookDiscount interface.

class DiscountManager {

void processBookDiscount(BookDiscount discount) {...}

}The refactored code follows the Open/Closed principle, as we could add the new CookbookDiscount class without modifying the existing code base. This also means that in the future, we can extend our app with other discount types (for instance, with CrimebookDiscount).

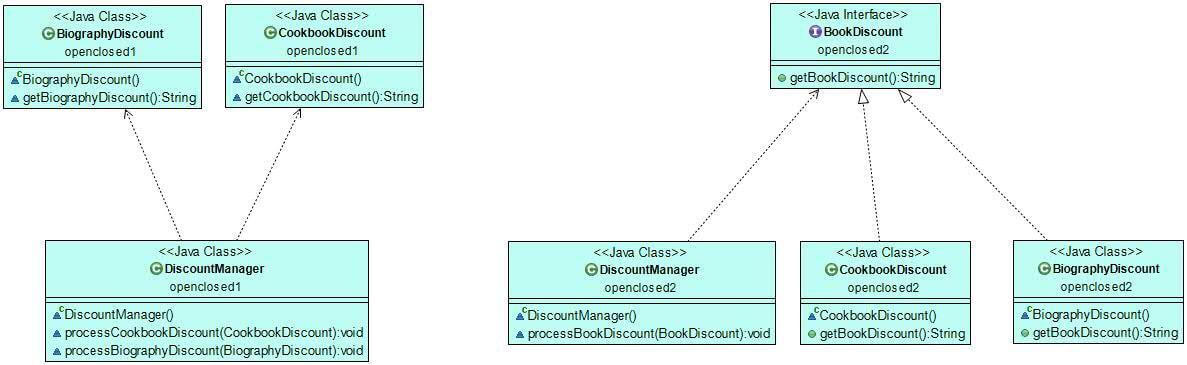

The UML graph below shows how our example code looks like before and after the refactoring. On the left, you can see that DiscountManager depends on the CookbookDiscount and BiographyDiscount classes. On the right, all three classes depend on the BookDiscount abstract layer (DiscountManager references it, while CookbookDiscount and BiographyDiscount implement it).

Liskov Substitution Principle

The Liskov Substitution Principle is the third principle of SOLID, represented by the letter “L”. It was Barbara Liskov who introduced the principle in 1987 in her conference keynote talk “Data Abstraction”. The original phrasing of the Liskov Substitution Principle is a bit complicated, as it asserts that:

“In a computer program, if S is a subtype of T, then objects of type T may be replaced with objects of type S (i.e., objects of type S may substitute objects of type T) without altering any of the desirable properties of that program (correctness, task performed, etc.).”

In layman’s terms, it states that an object of a superclass should be replaceable by objects of its subclasses without causing issues in the application. So, a child class should never change the characteristics of its parent class (such as the argument list and return types). You can implement the Liskov Substitution Principle by paying attention to the correct inheritance hierarchy.

Example of the Liskov Substitution Principle

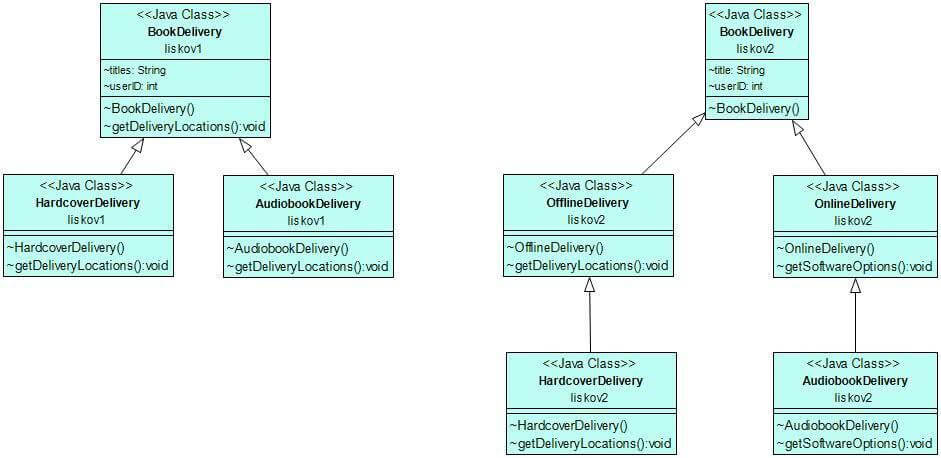

Now, the book store asks us to add a new delivery functionality to the application. So, we create a BookDelivery class that informs customers about the number of locations where they can collect their order:

class BookDelivery {

String titles;

int userID;

void getDeliveryLocations() {...}

}However, the store also sells fancy hardcovers they only want to deliver to their high street shops. So, we create a new HardcoverDelivery subclass that extends BookDelivery and overrides the getDeliveryLocations() method with its own functionality:

class HardcoverDelivery extends BookDelivery {

@Override

void getDeliveryLocations() {...}

}Later, the store asks us to create delivery functionalities for audiobooks, too. Now, we extend the existing BookDelivery class with an AudiobookDelivery subclass. But, when we want to override the getDeliveryLocations() method, we realize that audiobooks can’t be delivered to physical locations.

class AudiobookDelivery extends BookDelivery {

@Override

void getDeliveryLocations() {/* can't be implemented */}

}We could change some characteristics of the getDeliveryLocations() method, however, that would violate the Liskov Substitution Principle. After the modification, we couldn’t replace the BookDelivery superclass with the AudiobookDelivery subclass without breaking the application.

To solve the problem, we need to fix the inheritance hierarchy. Let’s introduce an extra layer that better differentiates book delivery types. The new OfflineDelivery and OnlineDelivery classes split up the BookDelivery superclass. We also move the getDeliveryLocations() method to OfflineDelivery and create a new getSoftwareOptions() method for the OnlineDelivery class (as this is more suitable for online deliveries).

class BookDelivery {

String title;

int userID;

}

class OfflineDelivery extends BookDelivery {

void getDeliveryLocations() {...}

}

class OnlineDelivery extends BookDelivery {

void getSoftwareOptions() {...}

}In the refactored code, HardcoverDelivery will be the child class of OfflineDelivery and it will override the getDeliveryLocations() method with its own functionality.

AudiobookDelivery will be the child class of OnlineDelivery which is good news, as now it doesn’t have to deal with the getDeliveryLocations() method. Instead, it can override the getSoftwareOptions() method of its parent with its own implementation (for instance, by listing and embedding available audio players).

class HardcoverDelivery extends OfflineDelivery {

@Override

void getDeliveryLocations() {...}

}

class AudiobookDelivery extends OnlineDelivery {

@Override

void getSoftwareOptions() {...}

}After the refactoring, we could use any subclass in place of its superclass without breaking the application.

On the UML graph below, you can see that by applying the Liskov Substitution Principle, we added an extra layer to the inheritance hierarchy. While the new architecture is more complex, it provides us with a more flexible design.

Interface Segregation Principle

The Interface Segregation Principle is the fourth SOLID design principle represented by the letter “I” in the acronym. It was Robert C Martin who first defined the principle by stating that “clients should not be forced to depend on methods they don’t use.” By clients, he means classes that implement interfaces. In other words, interfaces shouldn’t include too many functionalities.

The violation of Interface Segregation Principle harms code readability and forces programmers to write dummy methods that do nothing. In a well-designed application, you should avoid interface pollution (also called fat interfaces). The solution is to create smaller interfaces that you can implement more flexibly.

Example of the Interface Segregation Principle

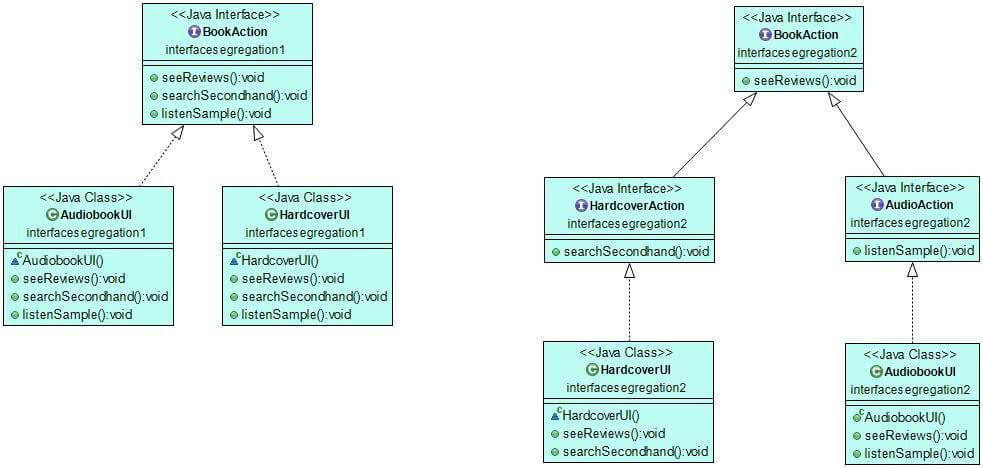

Let’s add some user actions to our online bookstore so that customers can interact with the content before making a purchase. To do so, we create an interface called BookAction with three methods: seeReviews(), searchSecondHand(), and listenSample().

public interface BookAction {

void seeReviews();

void searchSecondhand();

void listenSample();

}Then, we create two classes: HardcoverUI and an AudiobookUI that implement the BookAction interface with their own functionalities:

class HardcoverUI implements BookAction {

@Override

public void seeReviews() {...}

@Override

public void searchSecondhand() {...}

@Override

public void listenSample() {...}

}

class AudiobookUI implements BookAction {

@Override

public void seeReviews() {...}

@Override

public void searchSecondhand() {...}

@Override

public void listenSample() {...}

}Both classes depend on methods they don’t use, so we have broken the Interface Segregation Principle. Hardcover books can’t be listened to, so the HardcoverUI class doesn’t need the listenSample() method. Similarly, audiobooks don’t have second-hand copies, so the AudiobookUI class doesn’t need it, either.

However, as the BookAction interface include these methods, all of its dependent classes have to implement them. In other words, BookAction is a polluted interface that we need to segregate. Let’s extend it with two more specific sub-interfaces: HardcoverAction and AudioAction.

public interface BookAction {

void seeReviews();

}

public interface HardcoverAction extends BookAction {

void searchSecondhand();

}

public interface AudioAction extends BookAction {

void listenSample();

}Now, the HardcoverUI class can implement the HardcoverAction interface and the AudiobookUI class can implement the AudioAction interface.

This way, both classes can implement the seeReviews() method of the BookAction super-interface. However, HardcoverUI doesn’t have to implement the irrelevant listenSample() method and AudioUI doesn’t have to implement searchSecondhand(), either.

class HardcoverUI implements HardcoverAction {

@Override

public void seeReviews() {...}

@Override

public void searchSecondhand() {...}

}

class AudiobookUI implements AudioAction {

@Override

public void seeReviews() {...}

@Override

public void listenSample() {...}

}The refactored code follows the Interface Segregation Principle, as neither classes depend on methods they don’t use. The UML diagram below excellently shows that the segregated interfaces lead to simpler classes that only implement the methods they really need:

Dependency Inversion Principle

The Dependency Inversion Principle is the fifth SOLID design principle represented by the last “D” and introduced by Robert C Martin. The goal of the Dependency Inversion Principle is to avoid tightly coupled code, as it easily breaks the application. The principle states that:

“High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions.”

“Abstractions should not depend on details. Details should depend on abstractions.”

In other words, you need to decouple high-level and low-level classes. High-level classes usually encapsulate complex logic while low-level classes include data or utilities. Typically, most people would want to make high-level classes depend on low-level classes. However, according to the Dependency Inversion Principle, you need to invert the dependency. Otherwise, when the low-level class is replaced, the high-level class will be affected, too.

As a solution, you need to create an abstract layer for low-level classes, so that high-level classes can depend on abstraction rather than concrete implementations.

Robert C Martin also mentions that the Dependency Inversion Principle is a specific combination of the Open/Closed and Liskov Substitution Principles.

Example of the Dependency Inversion Principle

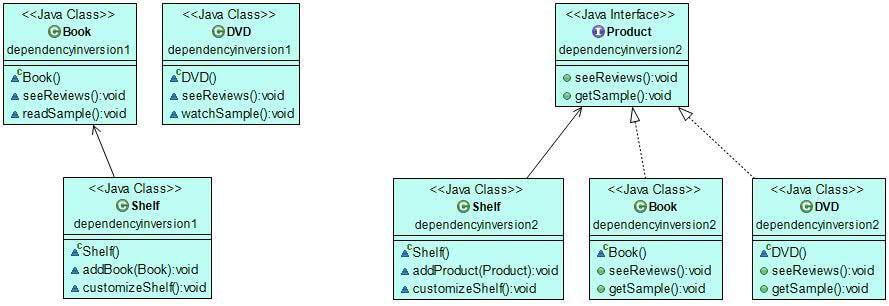

Now, the book store asked us to build a new feature that enables customers to put their favorite books on a shelf.

To implement the new functionality, we create a lower-level Book class and a higher-level Shelf class. The Book class will allow users to see reviews and read a sample of each book they store on their shelves. The Shelf class will let them add a book to their shelf and customize the shelf.

class Book {

void seeReviews() {...}

void readSample() {...}

}

class Shelf {

Book book;

void addBook(Book book) {...}

void customizeShelf() {...}

}Everything looks fine, but as the high-level Shelf class depends on the low-level Book, the above code violates the Dependency Inversion Principle. This becomes clear when the store asks us to enable customers to add DVDs to their shelves, too. To fulfill the demand, we create a new DVD class:

class DVD {

void seeReviews() {...}

void watchSample() {...}

}Now, we should modify the Shelf class so that it can accept DVDs, too. However, this would clearly break the Open/Closed Principle.

The solution is to create an abstraction layer for the lower-level classes (Book and DVD). We’ll do so by introducing the Product interface that both classes will implement.

public interface Product {

void seeReviews();

void getSample();

}

class Book implements Product {

@Override

public void seeReviews() {...}

@Override

public void getSample() {...}

}

class DVD implements Product {

@Override

public void seeReviews() {...}

@Override

public void getSample() {...}

}Now, Shelf can reference the Product interface instead of its implementations (Book and DVD). The refactored code also allows us to later introduce new product types (for instance, Magazine) that customers can put on their shelves, too.

class Shelf {

Product product;

void addProduct(Product product) {...}

void customizeShelf() {...}

}The above code also follows the Liskov Substitution Principle, as the Product type can be substituted with both of its subtypes (Book and DVD) without breaking the program. At the same time, we have also implemented the Dependency Inversion Principle, as in the refactored code, high-level classes don’t depend on low-level classes, either.

As you can see on the left of the UML graph below, the high-level Shelf class depends on the low-level Book before the refactoring. Without applying the Dependency Inversion Principle, we should make it depend on the low-level DVD class, too. However, after the refactoring, both the high-level and low-level classes depend on the abstract Product interface (Shelf refers to it, while Book and DVD implement it).

How should you implement SOLID design principles?

Implementing the SOLID design principles increases the overall complexity of a code base, but it leads to more flexible design. Besides monolithic apps, you can also apply SOLID design principles to microservices where you can treat each microservice as a standalone code module (like a class in the above examples).

When you break a SOLID design principle, Java and other compiled languages might throw an Exception, but it doesn’t always happen. Software architecture problems are hard to detect, but advanced diagnostic software such as APM tools can provide you with many useful hints.